Time-varying rates, or TVRs, include the variety of ways of conveying the time variation in utility costs and system load curves to consumers. In the U.S., the introduction of TVRs was spurred by the passage of the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act in 1978, which called on utilities and commissions to manage the growth in peak loads. Since then, the concept has continued to evolve in a series of “waves.”

First wave: Establishing peak versus off-peak pricing

Aided by funding from the federal government, several utilities conducted pilots with simple time-of-use rates, which featured higher prices in the peak period and lower prices in the off-peak period. The prices were known to the customer in advance and, in some cases, varied by season, but they did not vary dynamically in response to changing system conditions. In most cases, customers materially reduced peak consumption in response to the TOU rates, with very little (if any) load shifting to shoulder or off-peak periods. The reduction in peak consumption was statistically significant in many pilots. Higher peak-to-off-peak price ratios and shorter on-peak periods generally led to stronger customer response.

Second wave: Verifying connection between rates and behavior

In the mid-1980s, the Electric Power Research Institute examined the results from five of the best-designed pilots and found consistent evidence of consumer behavior response to the rates. Unfortunately, not much came of this discovery because of the lack of smart metering and because of the industry’s focus at the time on retail restructuring and the expansion of wholesale electricity markets.

However, a few utilities did move ahead with mandatory TOU rates for large residential customers. Virtually all utilities moved ahead with opt-in TOU rates, but few customers took advantage of the new rates.

Third wave: Introducing technology and dynamic pricing

The 2000–01 California energy crisis gave impetus to the next wave of pilots with TVRs. A statewide pricing pilot in 2003–04 showed that customers of the three investor-owned utilities in California reduced peak-period energy use in response to TVRs. This pilot was a game changer, helping to spur many more pilots around the globe. In addition to TOU rates, they featured other types of dynamic pricing designs. Some of these pilots featured enabling technologies such as in-home displays and smart thermostats.

This wave found that as customers’ peak-to-off-peak price ratio increases, customers reduce their peak consumption more, although at a declining rate. Studies in this wave also showed how enabling technologies, such as smart thermostats, significantly enhance customer responsiveness. The third wave of pilots also showed that customers with lower incomes can be price-responsive, although not to the same degree as the average residential customer.

Overall, the third wave of pilots yielded rich information on customer responsiveness to time-varying pricing. Pilots in the third wave provided the impetus and scientific evidence for widespread investment in advanced metering infrastructure.

Fourth wave: Scaling up

The fourth wave involved the large-scale rollout of TVR. Some rollouts featured two pricing periods, and others featured three pricing periods. Today, the ratio of peak to off-peak prices in 85% of the two-period TOU rates is at least 2:1, while the mean price ratio is 3:1. TOU rates with three periods have a similar price ratio as those with two periods.

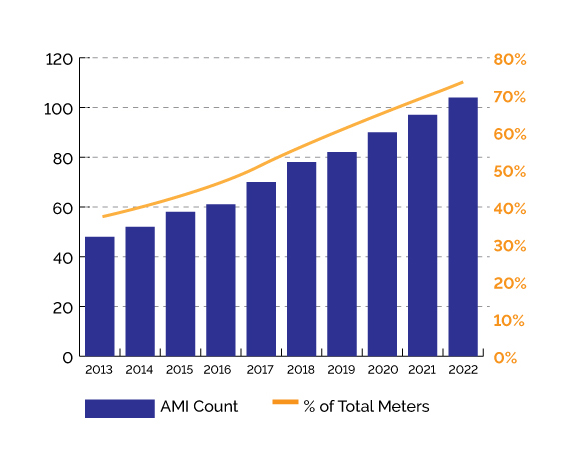

The implementation of TVR did not keep pace with the installation of AMI. According to the Energy Information Administration, 104.2 million households have AMI, which is about 73% of total residential electric meters as of 2022, but only 13.1 million households are enrolled on a TVR, about 9.4% of residential customers.

SMART METER INSTALLATION, 2013-2022

Where We Are Now

| Options for Easing Customer Transition to Time-Varying Rates |

|---|

|

Despite the evidence for TVR, there are persistent fears about a customer backlash or a failure to realize expected benefits in a full-scale deployment. Unless evidence of benefits is compelling, customers, utilities, and regulators will fear that the new rates will fail to promote economic efficiency or equity.

Utilities also need to address concerns among customers with specific situations, such as those with medical needs or those who have greater difficulty in managing their electricity consumption, and customers from disadvantaged groups.

There are ways to overcome these fears. Utilities can better understand the potential effects of the rate change by conducting bill-effect studies and customer behavior studies. Then, utilities can engage in customer outreach to explain why the electric rates are being changed and how the new TVRs will work. It is important to ensure the new rates use clear and understandable language.

Utilities can develop new and more efficient ways to communicate with their customers, especially the newer generations of technology-savvy customers. Embracing technology offers ways to connect with customers, and efforts such as developing apps and smart energy tools enhance the customer experience.

New technology is already beginning to reveal to customers the extent to which electricity cost can vary depending on usage patterns over time. Public policies and initiatives are opening the door for households to have more control over the source of their electricity — beyond retail choice — through distributed generation. Smart appliances, thermostats, and apps are giving residential customers more tools to control and customize usage patterns. Customers will still have the right to access reliable power supply, but these changes will continue to give households more power to optimize their individual electricity use, their cost of electricity, and their environmental footprint.

Also expect continued improvements in data exchanges from and to smart houses to give residential customers opportunities to capture value directly from wholesale electricity markets. This means that customers who install assets such as solar panels, battery storage, and load-flexible HVAC systems and appliances will not only react to wholesale market and system conditions, but they will actively participate in wholesale markets through agents or technologies that allow customers to communicate and coordinate directly with market administrators and system operators.

Not all customers will have the appetite for engaging in power supply decisions to this degree, but customers who are used to social media, fast-paced and complex communications, and a suite of apps to manage their lives will not find this foreign.

Ahmad Faruqui has been working on electricity pricing issues since 1979. In his career, he has consulted with utilities, regulators, legislators, and government agencies on six continents.